Research Article

Level and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Selected Seasonings and Culinary Condiments Used in Nigeria

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

3 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Federal University of Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Author

Author  Correspondence author

Correspondence author

Biological Evidence, 2018, Vol. 8, No. 2 doi: 10.5376/be.2018.08.0002

Received: 29 Mar., 2018 Accepted: 03 May, 2018 Published: 11 May, 2018

Aigberua A.O., Izah S.C., and Isaac I.U., 2018, Level and health risk assessment of heavy metals in selected seasonings and culinary condiments used in Nigeria, Biological Evidence, 8(2): 6-20 (doi: 10.5376/be.2018.08.0002)

Eight trace metals (Mn, Cd, Co, Zn, Cu, Pb, Cr and Ni) were analyzed in selected brands of seasonings and culinary condiments used for cooking in Nigeria with a view of determining the potential health risk index with regard to dietary intake and total hazard quotients. The samples were processed, digested and analyzed using flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The values of trace metals in the seasoning and culinary condiments were 0.11 – 1.52 mg/kg Cr, 0.76 – 3.56mg/kg Pb, 0.04 – 0.84mg/kg Cd, 0.52 – 2.87 mg/kg Ni, 0.06 – 2.60 mg/kg Cu, 0.27 – 7.86 mg/kg Zn, 0.68 – 56.64mg/kg Mn and 0.08 – 2.18mg/kg Co. The concentration of most 50% of the metals viz: Co, Zn, Cu and Ni were below the limit specified by Food and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization for food additives such as spices. The estimated daily intake values of the metals were less than the tolerable intake limits previously specified by various agencies including Institute of Medicine, Food and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization and European Food Safety Authority. In the four category of age grade, target hazard quotients (THQs) were <1 indicating no health risk concern for Zn, Cr and Pb; few of the samples had THQ >1 for Mn and Cu; majority of the samples also had THQ >1 with regard to Co and Cd; and school children and infants were at health concern for Ni from the consumption of the seasonings and culinary condiments. The summation of the THQ value of the metals were high, suggesting possible health concern for the consumers of this products on daily basis over a prolong period of time.

Background

Studies have variously shown that food is a major fundamental substance needed for growth of living organisms, development and effective functions of the various systems (Iweala et al., 2014; Izah et al., 2015a; 2016a; Izah et al., 2017a). Vitamins and minerals are some of the vital resources derived from food (Izah et al., 2017a). Authors have reported that food resources are classified based on their readiness for consumption i.e. ready to eat and food that requires processing before consumption (Izah et al., 2017a; 2015b).

Seasoning, spices and flavoring/culinary condiments are some resources used to improve the quality of food with regard to taste, fragrance/aroma, nutrition etc. Several foods are prepared with spices (Aigberua et al., 2018). Muhammad et al. (2011) described spices as vegetables materials of exotic and/ or native species with aromatic and hot piquant tastes used to add flavor to food. The authors further described seasoning as substances added to food to improve flavor, and they included salt, peppers and other spices. In recent times, the use of seasonings in food has increased especially in developing country like Nigeria. Seasonings used in food have the potential to replace notable item such as table salt in food. Furthermore, Etonihu et al. (2013) described condiments as food substances containing one or more extracts which are added to food to enhance flavor and it can either be compound (viz: chilli sauce, chutney, prepared mustard, meat sauce, mint sauce etc) or simple (viz: onion, garlic celery salts).

Seasonings have been widely applied in wide number of dishes including stew, jollof rice, soup etc made in commercial (restaurants, fast food outlets, and catering services) and home kitchen. Some notable seasonings commonly used include dried thyme, powdered curry, bouillon cubes, mixed spices, natural unprocessed spices i.e vegetables. Most of the seasonings contain plant materials as a major ingredient. Most common food seasonings and culinary condiments are used for cooking of meats (animal flesh), rice of various kinds (jollof, stew) and soups. Rice is one of the major sources of staple food in the world. While most families in developing country like Nigeria obtain their animal protein from chicken, beef and goat meats in addition to fish especially in urban areas.

Since most of the seasonings contain plants materials from pepper, carrot, nutmeg, onions, garlic, black pepper, parsley, mustard, sesame etc. as major ingredients, they contain several minerals such as calcium, potassium, magnesium and sodium (cations), trace metals (iron, copper, chromium, zinc, manganese etc which are essential metals and lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium which are also non essential metals). Different parts of the plants including leaves, fruit, flower, root, stem-back etc. are used for seasonings preparation depending on the producer and type of plant.

Typically, plants have the tendency to bioaccumulate toxicant such as heavy metals from their environment, thereby causing toxicity to the biota on exposure above recommended concentration (Aigberua et al., 2017). Izah and Srivastav (2015) reported that humans are exposed to heavy metals through ingestion from food and drinking water, dermal contact, inhalation and parenteral route. Among the various routes, Ihedioha et al. (2014), Seiyaboh et al. (2018), Kigigha et al. (2018) opined that food is the most common non-occupational heavy metals exposure.

Some heavy metals play vital roles in human health. The roles of these heavy metals (essential ones) and their roles, pathology and deficiency have been widely reported by authors (Palacios, 2006; Nnorom et al., 2007; Muhammad et al., 2011; 2014; Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a; Ihedioha et al., 2014; Prashanth et al., 2015; Asomugha et al., 2016; Izah et al., 2016b; 2017a,b; Izah and Aigberu, 2017). Several studies have been conducted with regard to trace metals in food substances and their associated health effects in Nigeria. Some of the food resources mostly focused on includes livers and kidneys of cattle (Iwegbue, 2008; Seiyaboh et al., 2018), spices (Iwegbue et al., 2011; Gaya and Ikechukwu 2016; Asomugha et al., 2016; Izah and Aigberua, 2017), chocolates and candies (Iwegbue, 2011a; Ochu et al., 2012), honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), canned fish (Iwebue, 2015), biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), milk (Iwegbue et al., 2013b), canned tomato paste (Iwegbue et al., 2012), wines (Iwegbue, 2014), canned beef (Iwegbue, 2011b), chicken meat and gizzard and turkey (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c), gari (Kigigha et al., 2018). But to the best of our knowledge information on health effects of packaged seasonings and culinary condiment used in Nigeria is scanty in literature. Hence, this study aimed at [i] assessing the level of trace metals in selected brands of seasonings and culinary condiment used in Nigeria, [ii] determining the dietary intake and target hazard quotients from the consumption of the seasonings.

1 Materials and Methods

1.1 Sample collection

A total of 13 brands of edible food seasonings and culinary condiments were purchased from retail outlets within Oil mill market, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. 3-4 samples of the same brands with different production date were purchased. Details such as ingredients/compositions, country of production and packaging of the 13 brands of seasonings is presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Seasonings ingredients, country of manufacture and packaging |

1.2 Reagents

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) 37 % (v/v) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), Nitric acid (HNO3) 69 % (v/v) Analar (BDH, Poole, United Kingdom), working standards of Mn, Zn, Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni, Co and Cr were prepared by diluting concentrated stock solutions of 1,000 mg/L (AccuNoHaz, New Haven, CT, USA) with 10% HNO3.

1.3 Sample preparation

The seasonings and culinary condiments were cut open from their polyethylene sachets. The ones in powdery and tiny leafy forms were grounded to powder. Then the seasonings samples were transferred into petri dishes with a stainless steel spoon spatula before being oven-dried in a Memmert U27 type drying oven at 70°C for 24 hours (Aigberua and Tarawou, 2017). Then after, 5 g dry weight of each sample was transferred into silica crucibles and dry-ashed in an Oceanic SX-2 type muffle furnace at a temperature of 450°C until the samples were greyish-ash. Samples were left to cool in a dessicator for about 30 minutes (Aigberua and Tarawou, 2017). A solution of the ash was prepared by acid digestion using 10 ml of 1 N HNO3 and 10 ml of 1 N HCl. The crucibles were covered with its covers made of silica, and it was heated at 120ºC for 60 minutes using hot plate until ash residue was completely dissolved. The digest was cooled to room temperature; the cover of the silica crucible was rinsed with 10 ml of 1 N HNO3 into the prepared ash solution. Then after, the digest was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The resultant filtrate was quantitatively transferred into a volumetric flask and made up to 25 mL with 10 ml of 1 N HNO3. A reagent blank containing acid mixtures used was prepared devoid of sample and all acid solutions were made up to 25 ml using distilled water (Aigberua and Tarawou, 2017). All samples and reagent blanks were aspirated into the GBC Avanta PM A6600 Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (FAAS) and the corresponding analyte concentrations were reported in mg/kg units.

1.4 Chemical analysis

The concentrations of Mn, Zn, Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni, Co and Cr in the ash solutions were analyzed using FAAS (GBC Avanta PM, A6600, Australia). The working conditions of the FAAS used to analyze the seasonings is provided in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Working conditions of the FAAS |

1.5 Quality control/assurance

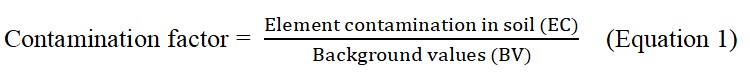

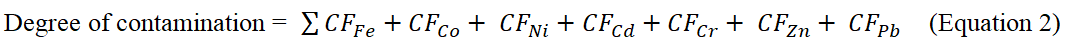

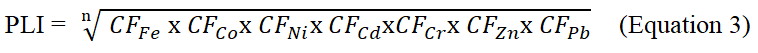

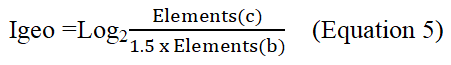

The quality assurance and quality control involves procedural blanks, replicate sampling and analysis and spike recovery method. The recovery was calculated based on equation 1. The spike recovery was carried out by adding a known analyte concentrations and reanalyzing the samples (Iwegbue et al., 2015a). The blanks were carried out for the respective metals under study using analytical method without the sample. The recovery values obtained ranged from 90.91% to 96.87% which is acceptable. Black was analyzed after the analysis of 7 samples of the seasonings and culinary condiments that have been dry-ashed and acid digested. The detection and quantification limits were assessed based on noise generated during the blank samples analysis. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were the level of analyte that provide a signal-to-noise ratio of 3 and 10 respectively. The LOD, LOQ, percentage spike recoveries of the various metals under study is presented in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Spike recovery, limits for the heavy metals analysis |

1.6 Health risk assessment

Health risk assessment has been widely applied in studies related to human health. The notable indices used for health risk assessment include total hazard quotients, health risk index and daily intake of metal. In this study, the health risk index were calculated in 4 criteria including adult (22-55 years with average body weight of 70 kg), under graduate (16-25 years with average body weight of 65 kg), school children (6-15 years with average body weight of 35 kg) (Ihedioha et al., 2014; Abubakar et al., 2014; Kigigha et al., 2017) and infants (1 - <6 years with average body weight of 15 kg) (Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

1.6.1 Estimated daily intake of metals

Estimated daily intake of metals has been widely calculated by authors (Orisakwe et al., 2012; Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a).

Where: Cmetal = concentration of heavy metal in the seasoning and culinary condiments sample (mg/kg); M food intake = daily intake of seasoning and flavoring condiments. The estimated maximum daily intake of 0.3 g for seasoning and culinary condiments in diets was used in this study.

1.6.2 Target Hazard quotients

Target hazard quotients is among the techniques used in investigating lifelong exposure to metals through diets (Iwegbue et al., 2013a; Ihedioha et al., 2014). Target hazard quotients were designed by United State Environmental Protection Agency to estimate potential health risk associated with long term exposure to chemical toxicant (US EPA, 1989). The Target Hazard Quotients were calculated have been widely applied by authors (Naughton and Petroczi, 2008a;b; Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a; Ihedioha et al., 2014; Kigigha et al., 2017, 2018).

Where:

1) EF=the exposure frequency (365 days/year) (Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a);

2) EDt=the exposure duration =48.9 years based on Nigerian life expectancy rate (Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a);

3) Mfi = Mass of seasoning and culinary condiments intake; Cm = concentration of metal in seasoning and culinary condiments;

4) RfD=oral reference dose for the metals under study were Cd (0.001), Pb (0.004), Cu (0.04), Zn (0.3), Cr (0.003), Mn (0.14), Ni (0.02), and Co (0.0004) (Iwegbue et al., 2013a);

5) BbW= body average weight for adult =70 kg (Abubakar et al., 2014; Ihedioha et al., 2014; Kigigha et al., 2017), 65 kg for under graduate (within 16- 25 years), 35 kg for School children (within 6-15 years) (Ihedioha et al., 2014) and 15 kg for child within 1-6 years (Iwegbue et al., 2015a);

6) AT=average time for non-carcinogen (days) (365 days/year) (Ihedioha et al., 2014; Iwegbue et al., 2013a, 2015a).

When the target hazard quotients is<1, it suggest no potential adverse effects (Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a; Ihedioha et al., 2014; Kigigha et al., 2017).

The summation of the individual target hazard quotient for seasoning and flavoring condiments is total Target Hazard Quotients (Iwegbue et al., 2013a; 2015a).

1.7 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was carried out using statistical package for Social Science. Data were expressed was mean ± standard deviation. The range (minimum and maximum) of the values for each seasonings and culinary condiments brand was presented in parenthesis. The resultant mean values of heavy metals concentration was used for the health risk assessment studies.

2 Results and Discussion

The level of the heavy metals in different brands of seasonings and culinary condiments is presented in Table 4. The heavy metals contents showed a wide range of variability according to brand. The variation that exists among the brands could be due to difference in feedstock, manufacturing processes and possible contamination from exogenous sources. Plants are major ingredient of seasonings and culinary condiments, as such it is possible that the plants may have absorbed the heavy metal from the soil they were cultivated.

|

Table 4 Heavy metal concentration (mg/kg) of selected spices used in Nigeria Note: Data were expressed as mean± standard deviation (n=7) |

The level of Cr in the seasonings under study varied from 0.11-1.52 mg/kg. The values reported in these seasonings were close to the range reported in variety of food products consumed in Nigeria. Some of previous values ranged from 0.001 – 3.81 in some Nigerian spices (Asomugha et al., 2016), 0.01 – 3.43 mg/kg in poultry products such as chicken meat and gizzard, and turkey meat (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), <0.01 – 10.8 mg/g in some imported candies and chocolates (Ochu et al., 2012), <0.25 – 55.25 mg/kg in honey consumed in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), 0.22 – 14.39 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue et al., 2015c), <0.01 – 1.21 mg/kg in milk products (Iwegbue et al., 2013b), 0.002 – 0.89 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 0.39 – 0.72 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012). But higher than the value of 0.01 – 0.10 mg/kg in canned sardines consumed in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2009), <0.001mg/kg in African giant snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c), 0.01mg/kg in some spices and vegetables in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2011), and 8.12 – 31.72 mg/kg reported in spices and vegetables sold in Yenagoa, Bayelsa state (Izah and Aigberua, 2017). Typically, Cr is an important mineral needed for biosynthesis of glucose tolerance factor (Prashanth et al., 2015; Izah et al., 2016b; 2017a). Long term exposure to higher concentration of Cr could lead to skin cancer and dermatitis, kidney, stomach, respiratory tract defects (Prashanth et al., 2015; Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

Pb concentration in the seasonings ranged from 0.76 – 3.56 mg/kg. Typically Pb is a non-essential metal as such its presence in the samples suggest toxicity. The values reported in this study were higher than 0.3 mg/kg recommended by WHO/FAO in food condiments such as spices (WHO/FAO, 2009; Batool and Khan, 2014; Asomugha et al., 2016). The Pb concentration recorded in this study had some similarity with the work of other authors on different food products. The findings of previous studies ranged from 2.61 – 8.97 mg/kg in edible part of some Nigerian spices (Asomugha et al., 2016), 0.01 – 4.60 mg/kg in poultry products such as chicken meat and gizzard, and turkey meat (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), <0.50 – 39.75 mg/kg in honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), 0.05 – 2.98 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue, 2015), 0.06 – 1.93 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 0.01 – 11.5mg/kg in some spices and vegetables (Iwegbue et al., 2011), 0.77 – 7.51 mg/kg in snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c), <0.3 – 1.82 mg/kg in canned tomato paste (Iwegbue et al., 2012), 0.001 – 1.07 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), but higher than the value of 0.002 – 0.40 mg/kg in milk products in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2013b), <0.001 mg/kg in some vegetables and spices (Izah and Aigberua, 2017). Typically Pb are known to hinder haemoglobin synthesis and cause several disorder leading to behavioral abnormalities, adverse effects on reproductive, neurological, hepatic, renal, hearing and learning processes (Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

The content of Cd in the seasonings ranged from 0.04-0.84 mg/kg. Like Pb, Cd is not required by biological diversity as such its concentration exceeding the 0.3 mg/kg recommended by WHO is an indication of toxicity (Ziarati, 2012; Batool and Khan, 2014). The value observed in the samples had some similarity with previous works on edible items. The Cd values in this study has some similarity with previous works that reported concentration in the range of 0.01 – 5.68 mg/kg in poultry products such as chicken meat and gizzard, and turkey meat (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), <0.3 mg/kg in honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), 0.17 – 4.20 mg/kg in vegetables and spices (Iwegbue et al., 2011), 0.11 – 0.26 mg/kg in canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), 0.002 – 0.11 mg/kg in milk products in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2013b), 0.04 – 0.83 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue, 2015), 0.002 – 0.49 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 0.03 – 0.05 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), but lower than the value of 0.99 – 3.28 mg/kg in snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c) and higher than the value of <0.001mg/kg in spices and vegetables (Izah and Aigberua, 2017). Cd is highly toxic and could lead to death of cells and/ or increase its proliferation (Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

The Ni concentration in the samples ranged from 0.52 – 2.87 mg/kg. The level of Ni was slightly above the content recommend for edible food items. The observed values were lower than 5.0 mg/kg recommend for edible spices by FAO/WHO (WHO/FAO, 2009; Asomugha et al., 2016). The values recorded in this study had some similarity with previous reports on food products. Some of these values ranged from 0.34-2.89 mg/kg in some food spices consumed in Nigeria (Asomugha et al., 2016), 0.13 – 7.97 mg/kg in some poultry products (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), <0.001 – 305.0 mg/g in candies and chocolates (Ochu et al., 2012), <0.2 – 6.98 mg/kg in honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), 0.4 – 3.26 mg/kg in canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), 0.01 – 16.8 mg/kg in spices and vegetables (Iwegbue et al., 2011), 0.03 – 1.94 mg/kg in milk products (Iwegbue et al., 2013b), <0.01 – 34.2 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue, 2015), 0.21 – 1.00 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 2.15– 4.88 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), but higher than the value of 0.03 – 0.40 mg/kg in snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c), and lower than the value of 5.01 – 16.03 mg/kg in spices and vegetables (Izah and Aigberua, 2017). Nickel is an important cofactor for several enzymatic processes in the body but higher concentration in the human body could be detrimental causing aggravated vesicular hand eczema (Ihedioha et al., 2014).

Cu was observed in the range of 0.06 – 2.60 mg/kg. The values were lower than the permissible limit 50 mg/kg for Cu (Nkansah and Amoako, 2010; Battol and Khan, 2014). Highest concentration of Cu was recorded in TCP. Higher concentrations have been recorded in some edible food products in Nigeria in the range of 3.0 – 4.2 mg/g in candies and chocolates (Ochu et al., 2012), <0.25 – 71.25 mg/kg in honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), <0.9 – 4.28 mg/kg in tomatoes (Iwegbue et al., 2012), <0.08 –1.51 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue, 2015), 0.01 – 0.20 mg/kg in spices and vegetables (Iwegbue et al., 2011), 0.04 – 0.12 mg/kg in snails (Iwegbue et al., 2008c), 1.85 - 3.55 mg/kg in vegetables (Izah and Aigberua, 2017), 1.41 – 7.19 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 0.53 – 5.04 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012). But the findings is in consonance with the value of 0.10 mg/kg in canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), 0.01 – 5.15 mg/kg in some poultry products (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), and higher than the value of <0.01 – 0.03 mg/kg in milk products (Iwegbue et al., 2013b). Cu is essential for several metabolic and biochemical processes including bone development, haemoglobin synthesis and connective tissue metabolism (Palacios, 2006; Prashanth et al., 2015). Cu deficiency could lead to anemia, mental retardation, changes in skeletal system (Prashanth et al., 2015).

Zn content observed in these samples ranged from 0.27 – 7.86 mg/kg. The Zn content was lower than the WHO/FAO limit of 50 mg/kg for edible spices (WHO, 2009; Asomugha et al., 2016). The concentration in this study was lower than the values of 14.09 – 161.04 mg/kg observed in some Nigeria spices (Asomugha et al., 2016), 4.95 – 48.23 mg/kg in some poultry products (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), <0.01 – 42.5 mg/g in candies and chocolates (Ochu et al., 2012), 0.09 – 4.63 mg/kg in canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), 0.25 – 10.75 mg/kg in tomatoes (Iwegbue et al., 2012), 1.15 – 17.88 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue, 2015), 1.63 – 14.98 mg/kg in vegetables (Izah and Aigberua, 2017), 0.69 – 1.25 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), but far lower than the value of 9.06 – 49.27 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), 30 – 44.02 mg/kg in spices and vegetables (Iwegbue et al., 2011), and higher than the value of 0.08 – 0.22 mg/kg in snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c). Zn play an essential role which depends on metalloproteinase present and they play essential roles in reproductive, neurological, dermatological, immune and gastrointestinal tract systems (Prashantha et al., 2015). It is also essential for the body including spermatogenesis and maturation, proliferation, differentiation and other metabolic activities of the cell (Prashanth et al., 2015), osteoblastic and alkaline phosphatase activities and collagen synthesis (Palacios, 2006). Zn deficiency is characterized by alcohol intoxication, acidosis, blockage of protein biosynthesis, compromised energy metabolism (Prashanth et al., 2015).

The concentration of Mn in the seasoning products ranged from 0.68 – 56.64 mg/kg. The values reported in this study were higher than the FAO/WHO maximum permissible limit of 2.0 mg/kg in food condiments such as spices (Inam et al., 2013). The values reported in other food products and condiments in Nigeria were within the range reported in this study. Some of the results of previous works ranged from 0.01 – 1.37 mg/kg in some poultry products (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), 0.64 – 1.37 in canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), 0.95 – 21.78 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue, 2015), 0.006 – 11.29 mg/kg in some canned fruit drinks (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 5.83 – 186.59 mg/kg in vegetables (Izah and Aigberua, 2017), 0.01 – 2.90 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), but lower than the value of 40.0 – 55.7 mg/g in candies and chocolates (Ochu et al., 2012), 11.0 – 31.75 mg/kg in honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b). Mn is a cofactor for several enzymes and it is required for biosysnthesis of mucopolysaccharides in bone formations (Palacios, 2006), fatty acids and cholesterol metabolisms, and oxidative phosphorylation (Prashanth et al., 2015). Deficiency of Mn is characterized by bleeding disorder (Prashanth et al., 2015).

The level of Co in the samples ranged from 0.08 – 2.18 mg/kg. The values were lower than the recommended value of 3.5 mg/kg in spices by WHO/FAO (WHO/FAO, 2009; Asomugha et al., 2016). The values observed had some similarity with previous works which were in the range of 0.28 – 3.07 mg/kg in some Nigeria spices (Asomugha et al., 2016), 0.01 – 1.37 mg/kg in some poultry products (Iwegbue et al., 2008a), 0.64 – 1.37 mg/kg in canned sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), <0.25 – 3.50 mg/kg in honey (Iwegbue et al., 2015b), 0.01 – 7.23 mg/kg in sardines (Iwegbue et al., 2009), 0.95 – 21.78 mg/kg in selected canned fish (Iwegbue et al., 2015c), 0.67 – 1.27 mg/kg in snail (Iwegbue et al., 2008c), <0.01 – 2.17 mg/kg in canned fish (Iwegbue et al., 2008b), 0.01 – 1.30 mg/kg in some brands of biscuits (Iwegbue, 2012), but higher than the value of 0.001 – 0.04 mg/g in milk (Iwegbue et al., 2013b), <0.001 mg/kg in vegetables (Izah and Aigberua, 2017). Co is an important component of vitamin B12 required for several processes (Iwegbue et al., 2015a). Co is also essential for methionine metabolism whereby it control the transfer of methyltransferase and homocysteine (Prashanth et al., 2015). Deficiency of Co is characterized by congestive cardiac failure, cardiomyopathy and pericardial effusion (Prashanth et al., 2015).

The estimated daily intake of selected trace metals from the consumption of 0.3 g of seasonings and culinary condiments for infants, school children, under graduate and adults is presented in Table 5. The daily intake of Cr varies from 0.000 – 0.030 µg/kg/bw/day. The values were lower than 5 µg/day required by adults (Prashanth et al., 2015). This translates to 0.071 µg/kg/bw/day for adults, 0.077 µg/kg/bw/day for under graduate, 0.143 µg/kg/bw/day for school children and 0.333 µg/kg/bw/day for infants. The values were lower than 200 µg/day daily intake recommended by joint FAO/WHO expert committee of food additives (JECFA) (WHO, 2013; Iwegbue et al., 2015a). Higher dietary intake of Cr has been reported in ready to eat food (Iwegbue et al., 2013a), chewing gum, peppermints and sweets in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

|

Table 5 Estimated daily intake of selected trace metals (µg/kg/bw/day) from the consumption of 0.3 g of seasonings and culinary condiments for infants (with body weight of 15 kg), school children (with body weight 35 kg), under graduate (with body weight 65 kg) and adults with body weight (70 kg) Note: Ad- Adult; UG-Under graduate; SC- School children; In-Infant |

Pb is not required by the human body. The daily intake for all categories under study ranged from 0.003 – 0.071 µg/kg/bw/day. The values were below WHO tolerable daily intake of 240 µg/day for adult with body weight of 68 kg (Garcia-Rico et al., 2007). The values were also lower than JECFA provisional tolerable daily intake of 3.6 µg/kg/bw/day (WHO, 2000; Iwegbue et al., 2013a, 2015a) which have been withdrawn (WHO, 2017). Higher level of Pb have been observed in some ready to eat food (Iwegbue et al., 2013a), chewing gum, peppermints and sweets sold in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2015a) and food supplements in Mexico (Garcia-Rico et al., 2007).

The daily intake of Cd from the seasonings and culinary condiments ranged from 0.000 – 0.017 µg/kg/bw/day. The values for all the scenarios were 100% less than WHO recommended daily intake of Cd (68 µg/day) for adult with body weight of 68 kg (Garcia-Rico et al., 2007), JECFA tolerable daily intake of 1 µg/kg/bw/day (Iwegbue et al., 2013a), provisional tolerable weekly intake of 2.5 μg/kg body weight (EFSA, 2011) which translates to daily intake of 0.35 µg/kg/bw/day (Iwegbue et al., 2015a), and provisional tolerable monthly intake of 0.5mg/kg/bw/month (WHO, 2017).

Ni daily intake of the seasonings and culinary condiments ranged from 0.002 – 0.057 µg/kg/bw/day for all scenarios. The obtained results were lower than recommended tolerable daily intake value of 1000 µg/day by Institute of Medicine (for adults between 19 - >70 years) (Institute of Medicine, 2001), 5 µg/kg/bw/day by WHO (Iwegbue et al., 2013a). In Nigeria, higher dietary intake of Ni have been reported in ready to eat food (Iwegbue et al., 2013a), chewing gum, peppermints and sweets (Iwegbue et al., 2015a) and food supplements in Mexico (Garcia-Rico et al., 2007).

The dietary intake of copper for all categories under consideration ranged from 0.000 – 0.052 µg/kg/bw/day. The values are far lower than the values recommended by Institute of Medicine (10000 µg/day) for adults within 19 - >70 years of age (Institute of Medicine, 2001), daily requirements for adults (2000 – 5000 µg/day) as specified by Prashanth et al. (2015) and provisional maximum tolerable daily intake of 0.5mg/kg/bw/day (WHO, 2017). The value of Cu is far lower than dietary intake from food supplements in Mexico (Garcia-Rico et al., 2007), ready to eat food (Iwegbue et al., 2013a), chewing gum, peppermints and sweets (Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

Daily intake of the seasonings and culinary condiments under all considerations for Zn ranged from 0.001 – 0.157 µg/kg/bw/day. The value is far lower than the values recommended by Institute of Medicine (40000 µg/day) for adults within 19 - >70 years of age (Institute of Medicine, 2001), 12000 µg/day recommended by National Research Council (1989), Iwegbue et al. (2015a), daily requirements for adults (15000 - 20000 µg/day) as specified by Prashanth et al. (2015), and provisional maximum tolerable daily intake of 0.3 mg/kg/bw/day (WHO, 2017). The values were lower than the findings of previous authors on ingestible food materials (Garcia-Rico et al., 2007; Iwegbue et al., 2013a, 2015a).

The dietary intake of Co from the samples under study ranged from 0.000 – 0.044 µg/kg/bw/day for all scenarios. The values for all categories were 100% less than recommended dietary allowance of 100 µg/day (Amidzic Klaric et al., 2011; Iwegbue et al., 2013a, 2015a). This value translates to 1.43 µg/kg/bw/day for adults, 1.54 µg/kg/bw/day for under graduate, 2.86 µg/kg/bw/day for school children and 6.67 µg/kg/bw/day for infants, and further lower than 0.1 µg/day recommended for adult by Prashanth et al. (2015).

The Mn concentration dietary intake for adults, under graduate, school children and infants ranged 0.02 – 1.133 µg/kg/bw/day. The values were lower than the daily requirement of 2000 – 5000 µg/day for adults (Prashanth et al., 2015). The values in this study were lower than the values previously reported in ready to eat food (Iwegbue et al., 2013a), sweets, peppermints and chewing gum in Nigeria (Iwegbue et al., 2015a).

The estimated target hazard quotients of selected trace metals from the consumption of 0.3 g of seasonings and culinary condiments for infants, school children, under graduate and adults in Nigeria is presented in Table 6. Trace metals such as Zn, Cr and Cd had THQ <1 indicating no health concern. THQ of Ni were <1 apart from some instances of school children and infants intake. Cd had THQ >1 in most of the seasonings and culinary condiments. Apart from GVP and TCP under infant consideration, the THQ were <1 for Cu. Furthermore, under all the scenarios, THQ of Mn were <1 apart from few instances, while THQ of Co were >1 in most of the samples. It is worthy to note that the interpretation of THQ values is binary (viz: 1

|

Table 6 Estimated target hazard quotients of selected trace metals from the consumption of 0.3 g of seasonings and culinary condiments for infants, school children, under graduate and adults Note: Ad- Adult; UG-Under graduate; SC- School children; In-Infant |

|

Figure 1 THQ from the ingestion of 0.3g of seasonings and culinary condiments for infants, school children, under graduate and adults |

3 Conclusions

The contents of most of the metals were below the values recommended for food additives such as spices. The estimated daily intakes from the ingestion of the metals through seasonings and culinary condiments were below tolerable level for each of the metals. Target hazard quotients were also <1 indicating no health risk concern for Zn, Cr and Pb; few of the samples were >1 for Mn and Cu; majority of the samples were >1 with regard to Co and Cd; and school children and infants were at risk for Ni from the consumption of the seasoning and flavoring condiments. The occurrence of some of these metals above the required limits is a source of concern, hence there is the need to establish regulatory limit for dietary intake of metals in seasonings and culinary condiments. Continuous surveillance of these seasonings with regard to heavy metal concentrations by relevant agencies such as standard organization of Nigeria (SON), National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) may help forestall the continuous influx of some unhealthy food seasonings and condiments currently in distribution within the market places in Nigeria.

Author’s contributions

Authors AOA and SCI conceived the idea. Author AOA procure the samples and carried out the laboratory analysis. Author SCI managed literature search, wrote the initial draft and managed correspondence. Authors IUI proof read the manuscript and corrected tense. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Anal Concept Limited Port Harcourt, Nigeria for providing the laboratory facilities to carry out this research.

Abubakar A., Uzairu A., Ekwumemgbo P.A., and Okunola O.J., 2014, Evaluation of heavy metals concentration in imported frozen fish Trachurus murphyi species sold in Zaria market, Nigeria, American Journal of Chemistry, 4(5): 137-154

Aigberua A.O., Alagoa K.J., and Izah S.C., 2018, Macro Nutrient Composition in Selected Seasonings used in Nigeria, MOJ Food Processing and Technology, 6(4): 0015

Aigberua A.O., and Tarawou T., 2017, Assessment of Heavy Metals in Muscle of Tilapia zilli from some Nun River Estuaries in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria, Academic Journal of Chemistry, 2(9): 96-101

Aigberua A.O., Ovuru K.F., and Izah S.C., 2017, Evaluation of Selected Heavy Metals in Palm Oil Sold in Some Markets in Yenagoa Metropolis, Bayelsa State, Nigeria, EC Nutrition, 11(6): 244-252

Amidzi Klaric D., Klaric I., Velic D., and Vedrina Dragojevic I., 2011, Evaluation of mineral and metal contents in Croatian Blackberry wines, Czech Journal of Food Science, 29(3): 260-267

https://doi.org/10.17221/132/2009-CJFS

Asomugha R.N., Udowelle N.A., Offor S.A., Njoku C.J., Ofoma I.V., Chukwuogor C.C., and Orisakwe O.E., 2016, Heavy metals hazards from Nigerian spices, Roczniki Panstwowego Zakladu Higieny, 67(3): 309-314

Batool S., and Khan N., 2014, Estimation of heavy metal contamination and antioxidant potential of Pakistani condiments and spices, Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, 5(3): 340-346

Etonihu A.C., Obelle F.N., and Nweze C.C., 2013, Chemical perspectives of some readily consumed spices and food condiments: a review, Food Science and Quality Management, 15: 10-19

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), 2011, Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Scientific Opinion on tolerable weekly intake for cadmium, EFSA Journal, 9(2): 1975

Garcı´a-Rico L., Leyva-Perez J., and Jara-Marini M.E., 2007, Content and daily intake of copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, and mercury from dietary supplements in Mexico, Food Chemistry and Toxicology, 45: 1599-1605

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2007.02.027

PMid:17418927

Gaya U.I., and Ikechukwu S.A., 2016, Heavy metal contamination of selected spices obtained from Nigeria, Journal of Applied Science and Environmental Management, 20(3): 681-688

https://doi.org/10.4314/jasem.v20i3.23

Hague T., Petroczi A., Andrews P.L.R., Barker J., and Naughton D.P., 2008, Determination of metal ion content of beverages and estimation of target hazard quotients: a comparative study, Chemistry Central Journal, 2

https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-153X-2-13

Ihedioha J.N., Okoye C.O.B., and Onyechi U.A., 2014, Health risk assessment of zinc, chromium and nickel from cow meat consumption in an urban Nigerian population, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 20(4): 281-288

https://doi.org/10.1179/2049396714Y.0000000075

PMid:25078345 PMCid:PMC4164878

Inam F., Deo S., and Narkhede N., 2013, Analysis of minerals and heavy metals in some spices collected from local market, IOSR Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences, 8(2): 40-43

https://doi.org/10.9790/3008-0824043

Institute of Medicine, 2001, Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Iweala E.E.J., Olugbuyiro J.A.O., Durodola B.M., Fubara-Manuel D.R., and Okoli A.O., 2014, Metal contamination of foods and drinks consumed in Ota, Nigeria, Research Journal of Environmental Toxicology, no volume, 1-6

Iwegbue C.M.A., Bassey F.I., Tesi G.O., Overah L.C., Onyeloni S.O., and Martincigh B.S., 2015a, Concentrations and health risk assessment of metals in chewing gums, peppermints and sweets in Nigeria, Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 9: 160-174

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-014-9221-4

Iwegbue C.M.A., Obi-Iyeke G.E., Tesi G.O., Obi G., and Bassey F.I., 2015b, Concentrations of selected metals in honey consumed in Nigeria, International Journal of Environmental Studies, 72(4): 713-722

https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2015.1028783

Iwegbue C.M.A., 2015, Metal concentration in selected brands of canned fish in Nigeria: estimation of dietary intakes and target hazard quotients, Environmental Monitoring Assessment, 187(3): 85

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-014-4135-5

PMid:25655121

Iwegbue C.M.A., 2014, A survey of metal contents in some popular brands of wines in the Nigerian market: estimation of dietary intake and target hazard quotients, Journal of Wine Research, 25(3): 144-157

https://doi.org/10.1080/09571264.2014.917616

Iwegbue C.M.A., Nwozo S.O., Overah C.L., Bassey F.I., and Nwajei G.E., 2013a, Concentrations of Selected Metals In Some Ready-To-Eat-Foods Consumed in Southern Nigeria: Estimation of Dietary Intakes and Target Hazard Quotients, Turkish Journal of Agriculture, Food Science and Technology, 1(1): 1-7

https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v1i1.1-7.1

Iwegbue C.M.A., Ossai E.K., Overah C.L., and Nwajei G.E., 2013b, Trace metals contents in some milk and milk products in Nigeria, Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering, 55(1): 101-107

Iwegbue C.M.A., Overah C.L., Nwozo S.O., and Nwajei G.E., 2012, Trace Metal Contents in Some Brands of Canned Tomato Paste in Nigerian Market, American Journal of Food Technology, 7: 577-581

https://doi.org/10.3923/ajft.2012.577.581

Iwegbue C.M.A., 2012, Mineral and trace element contents in some brands of biscuit consumed in southern Nigeria, American Journal of Food Technology, 7(3): 160-167

https://doi.org/10.3923/ajft.2012.160.167

Iwegbue C.M.A., Overah C.L., Ebigwai J.K., Nwozo S.O., Nwajei G.E., and Eguavoen O., 2011, Heavy metal contamination in vegetables and spices in Nigeria, International Journal of Biological and Chemical Science, 5: 766-773

https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v5i2.72150

Iwegbue C.M.A., 2011a, Heavy metal contents in some brands of canned beef in Nigeria, Toxicology and Environmental Chemistry, 93(7): 1341-1358

https://doi.org/10.1080/02772248.2011.587817

Iwegbue C.M.A., 2011b, Concentrations of selected metals in candies and chocolates consumed in Southern Nigeria, Food Additive and Contaminants Part B 4(1): 22-27

https://doi.org/10.1080/19393210.2011.551943

PMid:24779658

Iwegbue C.M.A., Arimoro F.O., Nwajei G.E., and Eguavoen O., 2009, Characteristic levels of heavy metals in canned sardine, Environmentalist, 29: 431-435

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-009-9233-5

Iwegbue C.M.A., 2008, Heavy metal composition of liver and kidney of cattle from southern Nigeria, Veterinarski Archives, 78(5): 401-410

Iwegbue C.M.A., Nwajei G.E., and Iyoha E.H., 2008a, Heavy metal residues of chicken meat and gizzard and turkey meat consumed in southern Nigeria, Bulgarian Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 11(4): 275-280

Iwegbue C.M.A., Nwozo S.O., Ossai E.K., and Nwajei G.E., 2008b, Heavy metals composition of some imported canned fruit drinks in Nigeria, American Journal of Food Technology, 3(3): 220-223

https://doi.org/10.3923/ajft.2008.220.223

Iwegbue C.M.A., Arimoro F.O., Nwajei G.E., and Eguavoen O., 2008c, Heavy metal content in the African Snail (Archachatina maginata (Swainson, 1821) (Gastropodia: Pulmonata Achatinidae) in southern Nigeria, Folia Malacologica, 16(1): 31-43

https://doi.org/10.12657/folmal.016.005

Izah S.C., Inyang I.R., Angaye T.C.N., and Okowa I.P., 2017, A review of heavy metal concentration and potential health implications in beverages consumed in Nigeria, Toxics, 5(1): 1-15

https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics5010001

PMid:29051433 PMCid:PMC5606672

Izah S.C., Bassey S.E., and Ohimain E.I., 2017b, Assessment of Some Selected Heavy Metals in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Biomass Produced from Cassava Mill Effluents, EC Microbiology, 12(5): 213-223

Izah S.C., and Aigberua A.O., 2017, Comparative Assessment of selected heavy metals in some common edible vegetables sold in Yenagoa metropolis, Nigeria, Journal of Biotechnology Research, 3(8): 66-71

Izah S.C., Kigigha L.T., and Anene E.K., 2016, Bacteriological Quality Assessment of Malus domestica Borkh and Cucumis sativus L. in Yenagoa Metropolis, Bayelsa state, Nigeria, British Journal of Applied Research, 01(02): 5-7

Izah S.C., Chakrabarty N., and Srivastav A.L., 2016b, A Review on Heavy Metal Concentration in Potable Water Sources in Nigeria: Human Health Effects and Mitigating Measures, Exposure and Health, 8: 285-304

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12403-016-0195-9

Izah S.C., Aseiba E.R., and Orutugu L.A., 2015a, Microbial quality of polythene packaged sliced fruits sold in major markets of Yenagoa Metropolis, Nigeria, Point Journal Botany Microbiology Research, 1(3): 30-36

Izah S.C., Orutugu L.A., and Kigigha L.T., 2015b, A review of the quality assessment of zobo drink consumed in Nigeria, ASIO Journal of Microbiology, Food Science and Biotechnology Innovations, 1(1): 34-44

Izah S.C., and Srivastav A.L., 2015, Level of arsenic in potable water sources in Nigeria and their potential health impacts: A review, Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques, 3(1): 15-24

Kigigha L.T., Nyenke P., and Izah S.C., 2018, Health risk assessment of selected heavy metals in gari (cassava flake) sold in some major markets in Yenagoa metropolis, Nigeria, MOJ Toxicology, 4(2):47–52

Kigigha L.T., Ebieto L.O., and Izah S.C., 2017, Health risk assessment of heavy metal in smoked Trachurus trachurus sold in Yenagoa, Bayelsa state, Nigeria, International Journal of Healthcare and Medical Sciences, 3(9): 62-69

Muhammad H.L., Kabir A.Y., and Adeleke K.B., 2011, Mineral elements and heavy metals in selected food seasonings consumed in Minna metropolis, International Journal of Applied Biological Research, 3(1): 108-113

Muhammad I., Ashiru S., Ibrahim I.D., Salawu K., Muhammad D.T., Muhammad N.A., 2014, Determination of some heavy metals in wastewater and sediment of artisanal gold local mining site of Abare Area in Nigeria, J Environ Treatment Techniq 1(3): 174-182

Muhammad I., Ashiru S., Ibrahim I.D., Salawu K., Muhammad D.T., and Muhammad N.A., 2014, Determination of some heavy metals in wastewater and sediment of artisanal gold local mining site of Abare Area in Nigeria, Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques, 1(3): 174-182

National Research Council (NRC), 1989, Recommended dietary allowance, 10th edn. National Academy Press, Washington

Naughton D.P., and Petroczi A., 2008a, The metal ion theory of ageing: dietary target hazard quotients beyond radicals, Immunity Ageing, 5: 3

https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4933-5-3

PMid:18492242 PMCid:PMC2438307

Naughton D.P., and Petroczi A., 2008b, Heavy metal ions in wines: meta-analysis of target hazard quotient reveals health risk, Chemistry Central Journal, 2: 22

https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-153X-2-22

PMid:18973648 PMCid:PMC2628338

Nkansah M.A., and Amoako C.O., 2010, Heavy metal content of some common spices available in markets in the Kumasi metropolis of Ghana, American Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research 1, 158-163

https://doi.org/10.5251/ajsir.2010.1.2.158.163

Nnorom I.C., Osibanjo O., and Ogugua K., 2007, Trace Heavy Metal Levels of Some Bouillon Cubes, and Food Condiments Readily Consumed in Nigeria, Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 6: 122-127

Ochu J.O., Uzairu A., Kagbu J.A., Gimba C.E., and Okunola O.J., 2012, Evaluation of some heavy metals in imported chocolate and candies sold in Nigeria, Journal of Food Research, 1(3): 169-177

https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v1n3p169

Orisakwe O.E., Nduka J.K., Amadi C.N., Dike D., and Obialor O.O., 2012, Evaluation of Potential Dietary Toxicity of Heavy Metals of Vegetables, Journal of Environment and Analytic Toxicology, 2: 136

https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0525.1000136

Palacios C., 2006, The Role of Nutrients in Bone Health, from A to Z, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 46: 621-628

https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390500466174

PMid:17092827

Seiyaboh E.I., Kigigha L.T., Aruwayor S.W., and Izah S.C., 2018, Level of Selected Heavy Metals in Liver and Muscles of Cow Meat Sold in Yenagoa Metropolis, Bayelsa State, Nigeria, International Journal of Public Health and Safety, 3: 154

Prashanth L., Kattapagari K.K., Chitturi R.T., Baddam V.R.R., and Prasad L.K, 2015, A review on role of essential trace elements in health and disease, Journal of Dr. NTR University Health Sciences, 4(2): 75-78

https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-8632.158577

US EPA, 1989, Guidance manual for assessing human health risks from chemically contaminated, fish and shellfish U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC EPA-503/8-89-00239

WHO, 2017, Evaluations of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives,

WHO, 2013, Summary and conclusion of the 61st meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) JECFA/Sc Rome, Italy 10-19 June, 2013

WHO/FAO, 2009, Corporate document repository plants as storage pesticides

Ziarati P., 2012, Determination of Contaminants in Some Iranian Popular Herbal Medicines, Journal of Environmental & Analytical Toxicology, 2: 1-3

. PDF(444KB)

. FPDF(win)

. HTML

. Online fPDF

Associated material

. Readers' comments

Other articles by authors

. Ayobami O. Aigberua

. Sylvester Chibueze Izah

. Isaac Udo Isaac

Related articles

. Dietary intakes

. Food seasonings

. Nigeria

. Target hazard quotient

. Trace metals

Tools

. Email to a friend

. Post a comment

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)